Posted on

I'm an experimental physicist, so part of my job entails writing software that orchestrates equipment in my experiment. Most of the code that runs my experiment is written in a proprietary scripting language that I guarantee none of you have ever heard of. The old code is brittle, difficult to debug, and generally makes it too much of a pain to add features unless absolutely necessary. Lately I've been thinking about how I would do a modernized rewrite in Python.

File: microperi.py Project: ntoll/microperi. Def getconnection: ' Returns an object representing a serial connection to a BBC micro:bit attached to the host computer. Otherwise, raises IOError. ' port = findmicrobit if port is None: raise IOError ('Could not find micro:bit.' ) serial = Serial ( port, 115200, timeout =1, parity ='N') serial. Write (b' x04') time. Sleep (0.1) serial. Write (b' x03') time. Sleep (0.1) serial. Readuntil (b' r ') time. Sleep (0.1) serial. CheckReadUntil read output of the command that I send to serial port until the sequence of symbols readUntil are in the serial output. Self.ser = serial.Serial(comDev, 115200, timeout=10). #Function that continue to read from Serial port until 'readUntil' #sequence of symbols appears def CheckReadUntil(self, readUntil): outputCharacters = while 1: ch = self.ser.read outputCharacters += ch if outputCharacters-len(readUntil):readUntil: break outputLines = '.

If you're working in an industrial, IoT, or scientific setting you might find yourself communicating with various devices via serial protocols. In my experience, ASCII-over-serial is the JSON of the scientific world in the sense that just about any piece of equipment you buy will have some sort of ASCII/serial support. For example, every single piece of equipment in my experiment uses ASCII-over-serial.

Lots of serial devices still default to a baud rate (bitrate) of 9600, or ~830us per character (byte). Your processor is running at several GHz. Furthermore, a read operation that times out will block the whole time it's waiting. Have some empathy for the machine. Give it permission to do something interesting when it would otherwise be dying of boredom.

I've written this article because despite asyncio blowing up the Python world, and despite pyserial (the de-facto serial library) providing an asyncio-compatible module, there is basically nothing written about how to actually use these two things together. Let's fix that.

A quick note before I get your hopes up: async serial doesn't yet work on Windows. Furthermore, the async serial functionality is listed as 'experimental,' so maybe don't bet your entire business on it.

Python Timeout Example

Alright, enough hedging, let's get down to business.

It would be a real shame if you needed a real serial device to even try this out. Luckily, some smart people made a tool called socat which lets you create virtual serial ports. Not only is this great for just tooling around, but it also means that you can test your serial-facing code in a CI environment as opposed to using a hardware loopback adapter or sticking a wire into the TX/RX pins of a serial cable (experimental physicists are half Einstein, half MacGyver).

This is the command I'll use to create a pair of virtual serial ports:

-d -dspecifies the logging level.-vwrites the data sent to each device to the terminal.ptyspecifies that the device should be a pseudoterminal.raweris the sound a lion makes.echospecifies whether each port should echo the data sent to it.linkis explained below.

When you run this command socat creates two virtual serial ports in /dev/ that are connected to one another, but it's not guaranteed to connect to those same devices every time. To make this more deterministic you can use the link= option which creates a symlink at to the device in /dev/. I've created two symlinks located at ./reader and ./writer so that I know exactly which paths to use when connecting to the serial ports in Python. There's a variety of other options that can be specified when using socat, so I encourage you to take a look at the docs if you're interested in learning more.

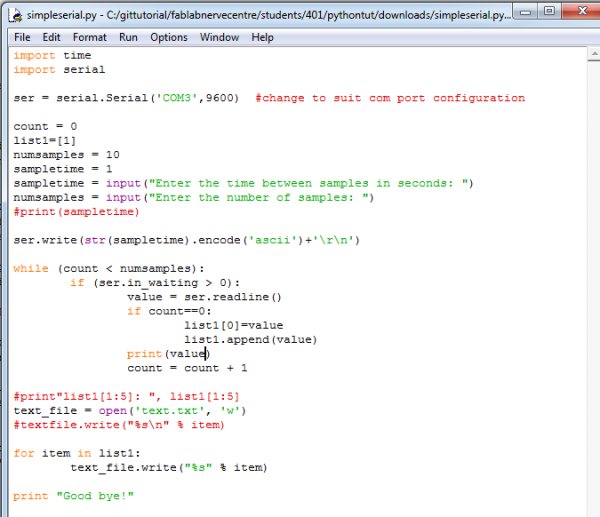

If you're using a serial port right now in Python, you're probably using the pyserial library to do something like this:

You create a Serial object by telling it which device to connect to and how the connection should be configured. Once you have the Serial object you can send or receive bytes from the serial port via the Serial.write and Serial.read methods respectively. To create a class representing some equipment that uses this connection, you can just pass the Serial object into the constructor.

You could of course just create the connection inside the constructor, but if your class takes the Serial object as an argument you can provide it objects configured in different ways in different situations i.e. configured to connect to /dev/something in production and configured to connect to /foo/bar in tests.

Aside: I will not be covering the basics of asyncio, that is beyond the scope of this post.

It would be great if pyserial-asyncio provided a magically async version of the Serial class, but that doesn't exist yet. Here is a list of what pyserial-asyncio does provide:

serial_asyncio.SerialTransportserial_asyncio.create_serial_connectionserial_asyncio.open_serial_connection

The SerialTransport class is a subclass of asyncio.Transport, and is really what allows all of this async serial stuff to work. Setting that aside, there are two ways to bring async to your serial code:

- Create a subclass of

asyncio.Protocolthat usesserial_asyncio.SerialTransportas its transport. - Generate an

asyncio.StreamReader/asyncio.StreamWriterpair.

I consider subclassing asyncio.Protocol to be the hard way, so we'll look at that first.

Alright, enough hedging, let's get down to business.

It would be a real shame if you needed a real serial device to even try this out. Luckily, some smart people made a tool called socat which lets you create virtual serial ports. Not only is this great for just tooling around, but it also means that you can test your serial-facing code in a CI environment as opposed to using a hardware loopback adapter or sticking a wire into the TX/RX pins of a serial cable (experimental physicists are half Einstein, half MacGyver).

This is the command I'll use to create a pair of virtual serial ports:

-d -dspecifies the logging level.-vwrites the data sent to each device to the terminal.ptyspecifies that the device should be a pseudoterminal.raweris the sound a lion makes.echospecifies whether each port should echo the data sent to it.linkis explained below.

When you run this command socat creates two virtual serial ports in /dev/ that are connected to one another, but it's not guaranteed to connect to those same devices every time. To make this more deterministic you can use the link= option which creates a symlink at to the device in /dev/. I've created two symlinks located at ./reader and ./writer so that I know exactly which paths to use when connecting to the serial ports in Python. There's a variety of other options that can be specified when using socat, so I encourage you to take a look at the docs if you're interested in learning more.

If you're using a serial port right now in Python, you're probably using the pyserial library to do something like this:

You create a Serial object by telling it which device to connect to and how the connection should be configured. Once you have the Serial object you can send or receive bytes from the serial port via the Serial.write and Serial.read methods respectively. To create a class representing some equipment that uses this connection, you can just pass the Serial object into the constructor.

You could of course just create the connection inside the constructor, but if your class takes the Serial object as an argument you can provide it objects configured in different ways in different situations i.e. configured to connect to /dev/something in production and configured to connect to /foo/bar in tests.

Aside: I will not be covering the basics of asyncio, that is beyond the scope of this post.

It would be great if pyserial-asyncio provided a magically async version of the Serial class, but that doesn't exist yet. Here is a list of what pyserial-asyncio does provide:

serial_asyncio.SerialTransportserial_asyncio.create_serial_connectionserial_asyncio.open_serial_connection

The SerialTransport class is a subclass of asyncio.Transport, and is really what allows all of this async serial stuff to work. Setting that aside, there are two ways to bring async to your serial code:

- Create a subclass of

asyncio.Protocolthat usesserial_asyncio.SerialTransportas its transport. - Generate an

asyncio.StreamReader/asyncio.StreamWriterpair.

I consider subclassing asyncio.Protocol to be the hard way, so we'll look at that first.

The asyncio module provides some helpful classes for handling asynchronous communication over a network connection. Two pieces of that puzzle are asyncio.Transport and asyncio.Protocol. A transport represents a type of connection, and handles the buffering and I/O. A protocol, which uses a transport, is generally responsible for telling the transport what to write, and for interpreting the data coming from the transport.

You tell your protocol how to behave by implementing a set of callbacks (see the docs for the list of callbacks). These callbacks are called by the transport in response to certain events i.e. when a connection is opened, when data arrives, etc. The default implementations of the callbacks are all empty, so we only need to override the methods that we're actually interested in. The callbacks we'll focus on are connection_made, connection_lost, and data_received.

Let's see an example. Suppose I have a device that produces ASCII messages that are terminated with a newline character, and suppose I want to read and print those messages. I'll make my imaginary device using one protocol subclass (Writer), and I'll read the messages it sends with another protocol subclass (Reader).

Writer

Here is the protocol subclass that will send the messages:

The connection_made and connection_lost methods will each be called once per connection. If you need to do any setup or teardown, those methods are a good place to do it. The transport passed to connection_made will be a SerialTransport, and it will have a field SerialTransport.serial that is a Serial instance. We'll use this Serial instance to read and write data to the serial port.

I've defined a coroutine function send that is responsible for sending messages a single character at a time with a delay of 0.5 seconds between characters. I've made send a coroutine function rather than a normal function because I want there to be a delay between characters, but calling time.sleep(0.5) would block the whole program, which kind of defeats the purpose when I'm trying to teach you about non-blocking I/O.

When you want to close the connection you call the Transport.close method, which will trigger the Protocol.connection_lost callback. I've sprinkled in some print statements so that if you run this on your own you'll see the flow of execution and things being scheduled on the event loop.

Reader

Here is the protocol subclass that will receive messages:

This time in connection_made I create an emtpy bytes object that I will use to store the received characters. For the sake of brevity I also store a count of how many complete messages I've received, and I'll use this as my termination condition since I know exactly how many messages that Writer will send (I designed it after all).

The interesting part of Reader is data_received. You aren't guaranteed whether you receive data byte-by-byte or in chunks, so doing the comparison data b'n' isn't guaranteed to work. Instead, I just add the new data to the buffer and then check whether there's a newline in there somewhere. If there is, I split the buffer on the newlines and increment the number of messages that have been received. I stop once I've read the number of messages that I know Writer will send.

The rest

I've shown you the interesting bits, so here's the rest of the stuff that you need to run the program (I've put the whole program on GitHub here):

Here I'm importing the requisite modules and setting all of the async stuff into motion. The create_serial_connection function takes a protocol subclass along with any arguments you want to pass to the constructor of Serial i.e. baudrate. The value returned by create_serial_connection is a coroutine object that creates connections to that particular serial port. Finally, I schedule the execution of the reader and writer coroutine objects, and schedule the loop to stop 10 seconds later.

If all goes well, you should see something like this in your terminal:

This is a pretty trivial example. Neither protocol needs to communicate with the outside world, so they basically just go off and do their own thing. Subclassing Protocol gives you lots of control over the behavior of the connection, but it's not immediately obvious how you get data out of your Protocol.

One method is to override the default constructor as a way of storing some kind of connection to the outside world. In the constructor you'll take an argument that is a resource shared between your protocol subclass and the rest of your code. This resource could be an asyncio.Queue, for instance. Here's how that would look:

In the constructor I store the queue, and in data_received I place complete messages onto the queue as they arrive. The create_serial_connection function won't pass anything to the constructor of your protocol subclass, so you'll need to somehow store the queue before handing the subclass to create_serial_connection. This is exactly the kind of problem that functools.partial was meant to solve. The partial function lets you specify some of the arguments to a function right now, and get back a function that takes the remaining arguments. In our case we're specifying the arguments to the constructor of Reader, and getting back something that will create Reader instances without needing any arguments.

I've modified the Reader/Writer example to use a queue as described above and put it here. This obviously works, but it feels like a lot of work to do something relatively simple. Isn't there an easier way?

I'm glad you asked! As mentioned above, subclassing asyncio.Protocol has its drawbacks. A simpler solution is to use the serial_asyncio.open_serial_connection function (note the difference in names: create_serial_connection vs. open_serial_connection) to generate an asyncio.StreamReader/asyncio.StreamWriter pair.

Python Serial Disable Timeout

There's no need to subclass anything, you just call a function. The url='' bit is a little odd (what do URLs have to do with anything?)1, but is just the name of the serial device i.e. /dev/ttysomething.

Using these two objects could not be easier. If you want to read from your serial device, you call one of the read coroutine methods on your StreamReader (read, readexactly, readuntil, or readline). If you want to write to your serial device, you call the write method on your StreamWriter. Let's see an example.

Streams and Queues

Let's say that I have two devices, reader and writer, and one of them will send messages to the other. Here's the entire program:

Python Serial Readline Timeout

In main I create my reader and writer objects, define the messages that will be sent, then create two coroutine objects for actually doing the reading/writing. At the end of main I say to wait for the reading and writing to finish before calling it quits.

I defined two coroutine functions send and recv, and each one does what it says on the tin. The send coroutine function takes a StreamWriter and a list of messages, then sends one message every 0.5 seconds. The recv coroutine function takes a StreamReader and tries to read until a newline character is encountered. If the message is DONE, then we pack up and go home, otherwise we print the message.

This is about as close as it gets to having a magically async-aware Serial class. In fact, if you wanted to make an async-aware Serial class, you could do it just by wrapping the various read and write methods of your stream reader/writer.

Well, that wraps things up. I recommend going the StreamReader/StreamWriter route unless you need fine-grained control over how your connection is handled. Another word of caution: make sure you actually need asyncio before you commit to it. There's a definite learning curve to asyncio, and it adds another layer of complexity. Having said that, go have some fun with asyncio and serial devices!

open_serial_connection calls create_serial_connection, which calls serial.serial_for_url, which will in most cases just call the Serial constructor with the arguments supplied to serial_for_url. open_serial_connection also requires that you specify all of its arguments as keyword arguments, but most of these arguments just get passed straight to serial_for_url. serial_for_url has a parameter called url, which gets passed to Serial as portname if you haven't specified a URL. So, the portname parameter of the Serial constructor comes from serial_for_url's url parameter all the way up in open_serial_connection.